-Shefali Vaidya

Today I got to know that Sadanandan Master, a dedicated RSS worker from Kerala, has been nominated to the Rajya Sabha. My heart swelled with joy, and with good reason. I have known Sadanandan Master for many years now and have admired his stoicism.

For anyone who has followed the blood-soaked trail of Communist politics in Kerala, Sadanandan Master is a living, breathing symbol of the triumph of human spirit. A living martyr they call him. His story is one that must be heard from his own lips. A few years ago, when the BJP fielded him as a Lok Sabha candidate from Kerala, I had interviewed him for Vivek magazine. I’m sharing his story again today as narrated by him to me.

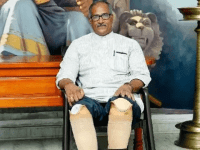

All of Kerala knows Sadanandan Master as a living martyr. Bespectacled, six feet tall, and still possessing a solid, powerful build even in his fifties, Sadanandan Master cuts an imposing figure.

When he is standing in his classroom lost in the world of history while teaching his students, you wouldn’t believe that both his legs have been severed from the knees down. For the past twenty years, he has walked with the aid of artificial limbs, but his spirit and his work ethic remain untouched, unshaken. His students fondly call him “Mashe”, and for this beloved teacher, there’s nothing his students won’t do. That’s how much they adore him.

When Sadanandan Master lost both his legs in 1994, he was just thirty years old. He did not lose his limbs in an accident nor was he suffering from any illness. He lost his legs in communist violence. Communist goons in Kerala brutally sawed off both his legs—right in the middle of a bustling marketplace.

His only “crime”? That he had dared to turn towards nationalist ideals, despite being born into a family steeped in Communist thought.

Sadanandan Master was the son of a committed Communist, but swayed by the Sangh’s nationalist ideals, he chose to become a swayamsevak. And he did this in Kannur district—the very heartland of violent Communist aggression in Kerala.

In this region, entire villages are designated as ‘party villages’, completely suppressed under the suffocating dominance of one ideology, Kerala brand of Communism, which is a deadly cocktail of communism, brutal violence and Islamic radicalism. Any whisper of an alternative thought is silenced through sheer, sadistic brutality. And yet, even in such inhospitable terrain, the seeds of nationalism are taking root, growing, blossoming—nurtured by the RSS. Sadanandan Master is the living embodiment of that blooming nationalism. This is his story, in his own words.

“I grew up in a small village near Mattanur in Kannur district. My father was a Communist Party worker. My elder brother was active in the youth wing of the Party. Naturally, I was raised on a diet of Marxist ideology. After all, Kannur is the ideological laboratory of Kerala’s Communism. The very first Communist thought in Kerala sprouted in the village of Pinarayi in Kannur. Kerala’s current Chief Minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, is from there—and he has himself been accused of political violence. The Communist Party has made it their policy that no other ideology should take root in Kannur.

If anyone even appears to lean towards any other ideology, they are methodically targeted—first through social and political ostracisation, then sabotage of livelihood, and finally, through unthinkable, brutal violence. This is the standard Communist playbook in Kerala. And yet, despite such terrifying opposition, the Sangh established a foothold in Kannur.

Youth like me, disillusioned with the thuggery and hollow promises of Communism, began turning towards the Sangh. We had seen firsthand the tireless efforts of the first generation swayamsevaks trying to establish the RSS in every village.

When I was in college, I was active in the SFI (Students’ Federation of India). But by then, it had become clear to me—Communism held no answers to the pressing issues of Bharat. Around this time, I met some RSS workers from my village. Their dedication to the nation, their efforts to find answers rooted in our own soil, deeply impacted me. Gradually, I began visiting the shakha.

My father did try to dissuade me, but he himself had grown weary of the Communists. Still, he feared for my safety. My former SFI friends, however, were outraged. They tried hard to “bring me back.” But I had seen through the façade—the arrogance, the attraction to violence, the brutal intolerance for opposing thought. I had made up my mind. I dedicated myself to working for the nation.

In our village, RSS workers had built a small bus stop with our own hands. That humble shelter became a symbol of the Communist government’s failure and the Sangh’s quiet strength. In September 1993, the Communists called for a bandh in Kannur. That day, some of their goons came to demolish the bus stop. We received word and rushed to the spot. A scuffle broke out. I was badly beaten.

The fact that we dared resist their hooliganism shocked them. Until then, they were used to unquestioned submission. And I, the son of a Communist, now a proud swayamsevak, was a thorn in their eye. They wanted to teach me a lesson I would never forget.

I remember that day with chilling clarity—25 January 1994. I was only thirty. My sister’s wedding was just days away. I was happy. My own engagement had recently been fixed—with Vanitha, my classmate from B.Ed. We were in love. We had completed our studies and were dreaming of a future together. We had no idea of what fate had in store.

That evening, around 8 PM, I returned to my village by bus. As I got down at the bus stop near my house, they were waiting for me. A party of Communist party goons. Some of them were my own neighbours. I knew them well. There was no personal enmity. Just blind, ideological hatred.

They surrounded me. Some lobbed country-made bombs to scare away onlookers. The street emptied. Then they pinned me down. And with a large, rusty carpenter’s saw, they severed both my legs below the knee. Even today, I cannot forget the excruciating pain.

But they didn’t stop there. They flung my severed limbs into the mud. They smeared dung on my bleeding knees—to ensure septic so that the doctors couldn’t reattach my legs. Their job done, they left me there, writhing in a pool of my own blood. I lay like an abandoned animal. Alone. Bleeding. Weak. I couldn’t even scream.

Half an hour passed before help came.

By the time the police arrived, I was barely conscious. They, along with fellow swayamsevaks, rushed me to a hospital in the city. Someone picked up my severed legs—not in hope of reattachment, but to show the doctors the brutality I’d faced. When I regained consciousness the next day, I saw that my knees were bandaged. And below that—there was nothing. Just the gaping silence of absence where my legs had been.

That same day, Vanitha came to see me. Her face was wrecked with grief. Summoning all my courage, I told her I was releasing her from all promises. That she shouldn’t marry a cripple like me. Her parents said the same. But she simply shook her head in a firm no.

I spent almost six months in the hospital. Those were the darkest days. I had done no wrong. Why had I been singled out for such agony? Depression sank its pointy claws in me. I contemplated ending my life. But Sangh karyakartas came to visit me daily. They spoke to me. Kept my mind engaged. I would hum shakha songs to myself, trying to gather courage.

Through all this ordeal, Vanitha never left my side. Not even once. Her unwavering love, my family’s quiet strength, and the Sangh’s relentless support pulled me out of the abyss. Doctors fitted me with Jaipur Feet.

I slowly began learning to walk again. Every step was a storm of pain. My skin would peel where the artificial foot would rub against it. My muscles would scream. Phantom pain would make me scream. But I pushed through. The day I took four steps on my own, without support, was a celebration not just for me, but for my family, Vanitha and for every swayamsevak who had stood by me.

It’s been more than twenty years now. I work eighteen-hour days, every day. I teach standing up for hours. I travel by whatever means I can. I’ve forgotten I don’t have real legs. Vanitha and I got married. We built a modest home. We have a daughter—she’s doing her B.Tech. I still work for the Sangh. I have my family’s full support. Even they now understand the depth of nationalist thought. Even some of the men who attacked me have moved towards the Sangh.

Some of them came and apologised to me later. I don’t hate them. The fault isn’t theirs. It’s their communist ideology that blinded them with hate. Today, I teach young students. I have no desire to pass on the poison of hatred. The Sangh teaches love for the nation, not hatred for any individual or group. I want my students to love this land, this soil. Not imported ideologies with foreign roots. I want them to seek solutions to our problems from our own civilisational wisdom.

Since Pinarayi Vijayan became CM, political violence in Kerala has surged again. What else can one expect from a state where the CM himself faces murder charges? The challenges facing nationalist forces in Kerala are grave. On one side, Communist bloodlust. On the other, creeping Islamic fundamentalism. In some regions, unchecked Christian evangelism.

And yet, the flame of love for the nation continues to burn in Kerala. After all, this is the land of Adi Shankaracharya. The RSS’s influence is growing—slowly, but surely. I’m confident that in a few years, things will change.”

And now, Sadanandan Master—the man who stood tall even after being cut down—is chosen today as a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha by the president of Bharat. What a journey. What a man. What an inspiration for generations to come!

Leave a comment